When Nanoparticles Learn to Talk: Building a Rosetta Stone for the Human Immune System

Researchers from the UNC Charlotte Klein College of Science discovered how to translate a new language to unlock human immunology, in the first ever study to decode microglia, the cells of the brain’s immune system.

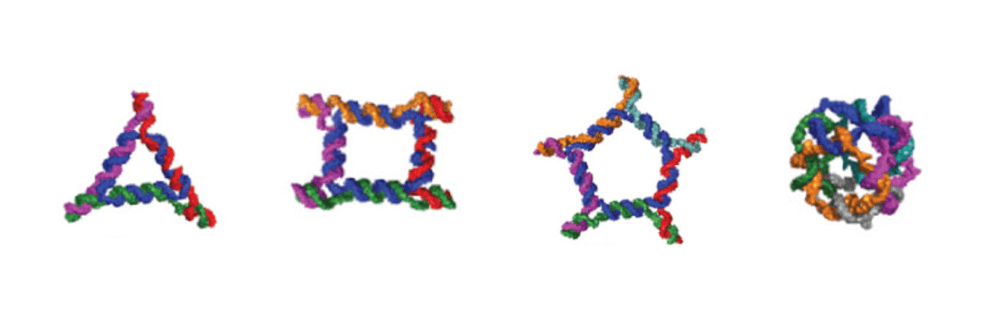

This translator allows scientists and clinicians to compose messages in the immune system’s language by deciphering how different immune cell “dialects” generate responses. The patient’s immune system will induce a personalized response, based on the communication from tiny nucleic acid nanoparticles (NANPs), specific to their unique needs.

Delivering the right message can save treatment time by anticipating how the immune system will react and deliver the precise response needed.

“To put it in analogy: think of the immune system as a large, diverse neighborhood of cells like monocytes, dendritic cells, macrophages or similar; each group speaks the same language with subtle dialect variations. The NANPs are like short encrypted messages defined by the nanoparticles’ size, shape and composition as well as how they are delivered.”

Kirill Afonin, team leader and professor of chemistry

The team’s earlier work studied the language of blood cells for the circulatory system. The newest study “From Sequence to Response: AI-Guided Prediction of Nucleic Acid Nanoparticles Immune Recognitions,” was published in Small, one of the leading nano and micro technology journals, and it adds a translation for the central nervous system (CNS), decoding the language of microglia.

“Microglia are part of the home security system for the CNS. These cells constantly monitor the CNS for signs of infection, inflammation, or damage. These studies are especially exciting because limiting damaging off-target effects and a lack of predictive models are major challenges for developing therapeutics for CNS disorders and diseases.”

Brittany Johnson, assistant professor of biology

The Discovery

The team’s study used a carefully prepared set of 176 unique NANPs to train a computational model. The researchers can now anticipate how the recipient cell types will respond when they open the message, and choose the appropriate response.

This newest translation is a major step toward rational immunomodulatory design. A message might:

- Scream loudly, launching a “stranger danger” alarm that would flood the area with inflammatory signals in a cytokine storm

- Whisper quietly, encouraging the cells to “keep calm and carry on” and ignore the message, to keep inflammation down

- Send a professional and measured message, asking for a moderate response in a “Goldilocks” just-right way

Instead of sending “spam” messages blindly and hoping for the best outcomes with immune response, scientists can now sketch the shape of their NANPs and run them through the AI-cell translator.

Within a few seconds, they can choose from designs that either minimize immune activation for drug delivery where stealth is needed, or maximize activation for immunotherapy where robust immune engagement is needed.

“The immune system is both a friend and a potential foe. If we don’t anticipate how it will respond, the risk of unwanted inflammation or inefficient payload delivery may endanger the therapeutic outcome.”

–Brittany Johnson

The team developed the first generation of the model, called the Artificial Immune cell or “AI-cell,” that used a library of NANPs with known physicochemical features (size, nucleic acid type, architecture, delivery vehicle) and their known immune responses, to predict how much interferon a new NANP might trigger in monocytes.

The new translation expanded the team’s previous work in several important ways:

- Built a larger data set: To accurately predict responses from even more variations of NANPs, with distinct and wide-ranging structural and compositional differences.

- Upgraded the model: The transformer-based deep-learning architecture captures more complex relationships between NANP features and immune outcomes.

- Added a new dialect: The immune readouts now include human microglia cells, key players in addressing many CNS disorders and infections.

“The overarching goal is to advance the AI-cell platform beyond focusing on single immune cell types and to build predictive models that capture the full ‘language’ of immune responses triggered by NANPs and interpreted across different tissues and cell types, ultimately understanding the immune responses of every system in the human body,” said Afonin.

The current AI-cell work focused on one dialect that is understood by human microglia. The further development of the AI-cell open access platform will cover multiple dialects, predicting a richer vocabulary of cytokine responses across more cell types.

This moves the field closer to “multilingual immune design” of smart NANP therapies.

Applications for the Future

Some of the broader implications for the field of therapeutic nucleic acid nanotechnology, which is a major interest of the Afonin lab, are significant:

- Faster design cycles: Researchers can save weeks of time by running many AI-cell predictions in only seconds, prune poor designs up front and focus experimental work on the most promising NANPs.

- Safety engineering: AI-cell offers the ability to forecast immune signatures for non-immunogenic carrier NANPs which can bring fewer surprises in later studies.

- Tailored immunotherapies: AI-cell can tune NANPs to produce a predetermined cytokine profile for needed immune activation (e.g., cancer vaccines).

“The immune system is complex, and in vitro predictions may not always map perfectly to in vivo realities: biodistribution, organ-specific responses, protein-corona formation, prior immune exposures are other factors that will influence how the immune system interprets your NANP in real life,” said Afonin. “The AI-cell tool is only as good as its training data: if certain cell types, delivery vehicles, or species are not yet tested, the predictions will be weaker in those regimes.”

In essence, the current “translator” is very good, but the conversation remains complex and needs to be constantly upgraded with additional research. Just as we might learn multiple languages to communicate with different human communities, the NANP technology learns to speak multiple “immune-dialects” so that we can engage many different monocytes, dendritic cells, or macrophages according to specific therapeutic needs.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R35GM139587 and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The findings and conclusions in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views or policies of the NIH, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, or the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The work was also supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the NIH under Award Number R15EB031388 and, in part, by the Intramural/Extramural Research Program of the NCATS, NIH.